Archéologie de l'architecture, de l'enfance, de l'histoire, du corps, des temps

1998 - 2005

Lamento

Lamento est un recueil de cinq textes tirés de l'ouvrage du même nom, édité par le Musée d'Art Moderne Grand-Duc Jean, (Mudam Luxembourg), à l'occasion de l'acquisition du Musée des trois sculptures de Pascal Convert autour de la question de la photographie de presse.

"Construire la durée" / "Constructing duration" / "Die Konstruktion der dauer" Georges Didi-Huberman

"Images passages" / "Passageway images" / "Durchgangsbilder" Pascal Convert

"Eloge des aérolithes" / "In praise of aeroliths" / "Lobrede auf due himmelssteine" Philippe Dagen

"L'orphelinat des images" / "The orphanage of images" / "Das wisenhaus der bilder" Bernard Stiegler

"Pascal Convert

or

How to Get Free of the Real",

Catherine Millet

Since this is a person who deals in and with images, why not start with his image, as a person? The first time I saw Pascal Convert's face, quite a while ago now, it struck me as somehow incongruous in the festive atmosphere of the dinner where we were guests. It was a sorrowful face, a bit alarmed-looking too, because there was, perhaps, an unbridgeable gap between the cause of the sorrow that furrowed his brow and the spectacle now before him. Since then he and I have become friends and I have stopped counting the times I have sat opposite him at lunch or dinner, always facing that mobile forehead which tortures his eyebrows, even when the subject ofconversation is an amusing one. I have stopped being surprised because I realise now that Pascal's is the face of a speleologist. His brow, like his hair and always rather shaggy beard (sorry, Pascal), bears witness to the effort he has had to make to pull himself out of the deep tunnels where he has descended in his attempts to get to the bottom of humanity, and his big, staring eyes behind his glasses are those of a man who can still hardly believe he is in the light again.

The speleologist has brought back some fossils from his expedition. The notable thing about these fossils is that they are the same size as we are. They are therefore very close to us. We might be tempted to lodge ourselves in the finely hollowed imprint. But at the same time they are also very remote, so remote that our gaze cannot grasp them.

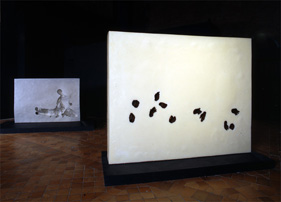

There are, at the time of writing, three such fossils, three highly paradoxical objects: set in big wax parallelepipeds, they are life-size imprints of human bodies based on their image in 24x36 photographs or in a video still. They were first presented at an exhibition about photography and the general relation between the visual arts and photography. Visitors noted the weight of their presence. Critics, and especially photography critics, were struck by the fact that these works put back into the concrete world bodies that had been caught up in that circulation of media which, they say, increasingly disembodies its objects, to the extent that it pushes them into the virtual world (1). hese bodies had been bruised, massacred or hystericised - crushed by war (Kosovo, Algeria, the Gaza Strip), but at the same they had been captured by reporters' lenses and transformed into icons. Now, to add paradox to paradox, these fossils, these two-ton sculpted forms, based on photographic images, do not so much restore reality to those images as, on the contrary, make the emptying of reality acutely perceptible.

As for the idea that came to me, it is in fact a quotation from Saint Paul that Jacques Henrie took as the title of one of his novels: Car elle s'en va la figure du monde ("For the fashion of this world passeth away'') (2). The novel relates a filmmaker's incapacity to make just a simple shot of hands. Life eludes his lens. Going back to the book, I came upon this passage: "Wanted to photograph real trees. But what always show up on the photo are blackened blobs. Blocks of unparticled matter. Dark ink blots of magnetised blood." In 1995-96 Pascal Convert made some sculptures using tree stumps, which he had gathered in the forest at Verdun, then covered with Indian ink, which seemed to fix them like a varnish. Although these were three-dimensional works, the stumps could easily have illustrated that passage in the novel. It was as if the shadow of the backlit object, characteristic of photography, had taken over these objects.

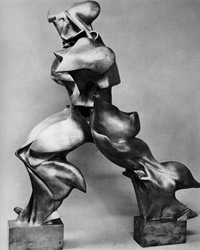

Immersed in the viscosity of the real, Convert was concerned with the question of realism (3) : How to avoid making "war memorials"? Why was realism colonised by totalitarianism? It is noteworthy that while humankind has spent nearly a century developing the most effective machines for destroying the real, artists should have continued to concern themselves with representing it, while at the same time avoiding commemoration and propaganda. In the middle of the last century, there was even a school called Nouveau Realisme (New Realism). And what was the technique used by its leader, the artist Yves Klein? The imprint. Some of his finest works, theAnthropometries, are formed by the traces of his models' nude bodies pressed against the canvas. Following the same trend as Nouveau Realisme, Roy Adzak made his negative Imprints, wooden or plastic blocks and slabs hollowed out by the form of an object or body. Adzak had worked on archaeological digs and, one morning, could have sworn that he saw the amphora they had dug up the day before back in the earth. In fact, it was simply the space left by the object. "This absence of the object", concludes Iris Clert in her telling of the story, "was just as real as the object itself." (4). The imprint has as much, if not more reality than the real object or body, which is always bound to have taken a few knocks anyway. Already, at the dawn of the modern period, Manet- if we follow Bataille's reasoning- had tried this approach in his Execution of Maximilian, a painting famous for its total lack of eloquence, and that says nothing about the horror of the death it depicts, but instead "attains it by absence" (5). Bataille comments on Malraux, according to whom Manet "never managed to make something out of Maximilian". Comparing this painting to Goya's Third of May, Malraux considers that Manet fails to equal the eloquence of his model (Manet was familiar with Goya's painting). But could we not think that if, according to Malraux's criterion, Manet "never got free of Maximilian", it was because his primary objective was to make something out of the viscous real?

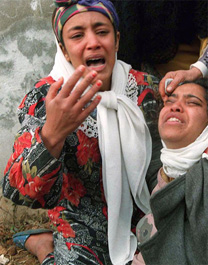

All three of Pascal Convert's sculptures are inspired by images of current events: a photograph by Georges Merillon from 1990 (Veillee funebre au Kosovo [Mourners at the deathbed of Elshani Nashim]), a photograph by Hocine Zaourar from 1997 (Massacre a Bentalha [A woman cries outside the Zmirli Hospital]), and a still from footage shot in 2000 by the cameraman Talal Abou Rahmeh (the death of the little boy Mohamed Al Dura). However, each of these images is transposed into the thickness of the wax in a distinct way. For example, the composition of the wake in Kosovo is reversed in relation to that of the photo, as if the wax were the mould of the reality captured by the camera! But this impression of direct contact with reality is mitigated by the highly abstract effect of the hands. The artist seems to have changed the angle from which they are seen in the photo, making them look more open and spread out over the surface of the sculpture. These hands are all the more striking because they are "represented" by the deepest hollows in the wax - black holes surrounded by copper. They are almost hypnotic, like those hands of figures in Byzantine paintings that jut out from the regular folds of their robes. Such hands are like signs, almost a kind of writing. As the only expressive elements, the beholder struggles to connect them with the bodies they belong to, so uninhabited do the stylised dresses here seem. The hands in Convert's sculpture, too, draw the gaze. It is not that they are pointing it to something; rather, they cause it to lose itself in their gaping openness.

In this set of works, the most baroque ensemble is clearly that of the two women in the Madona of Bentalha. Their absent bodies are dressed in shawls and coats that here become a sumptuous relief, the only one among the three sculptures. And since these women inevitably bring to mind Bernini's Saint Teresa, the resulting erotic contamination turns the gesture of support by the woman in black into a caress of her companion's breast, no more emphatic than a hand print in the sand. But when the viewer breaks free of the fascination exerted by the billowing folds of the robes, and tries to look more closely at the faces, then the feeling of abandon communicated by this work, of voluptuous abandon in even the most terrible suffering - or precisely because it is the most terrible - switches abruptly into something vertiginous. Seen from a certain angle, the inverted relief of the grief-stricken woman looks like a funnel. In other words, the mouth opens monstrously like an air vent, so that the cry now seems to be sucked back in and smothered. When looking through Convert's own archive of images, I realised that he collects photographs of open mouths: the mouths of children and women open with fear, as they weep. Perhaps the idea of making his embossed sculptures came to him when examining these images in which the cry pushed out from the depths of the chest, but no longer audible, is reversed and becomes a wound opening the flesh.

The treatment of single body formed by the prostrate boy Mohamed and his kneeling father is much more restrained. It forms a right angle, placed in the lower right part of the slab of wax, leaving the rest bare. The arms and legs that, in the video still, were bent forward, become in the sculpture deep, terrifying galleries, leading into the unknown, to the other side of the surface that is presented to us. Going round to the other side, we see where they enigmatically emerge, giving onto nothingness. They are like those entrails that surprise us when they appear on the screen, thanks to the optical fibre that now explores our viscera. Of the three sculptures, it is the one of Little Mohamed that most gives us the sensation of experiencing the scene, although we cannot see it from within the bodies, and are indeed their prisoners. Just as the shot, extracted from the film, is framed fairly close to the bodies and offers no access to the context in which they are involved, so the smooth surface of the block of wax constitutes a screen that keeps us from seeing what is happening on the other side, on the side where the folded knees have vainly attempted to protect the rest of the body. And so our gaze has no choice but to take refuge in the crevices of these empty shells that are the man and his child, since they themselves are huddling in an illusory niche. And we are as blind to the rest of the scene as they may have been in the real-life situation.

Of course, what I have just described are only moments of seeing these works. The displacement of the shadows in the concave forms, as we move laterally along the slabs, is constantly remodelling our perception of them. I mentioned the fact that, in front of the women of Bentalha, we go from a vision of sensuality to that of a gaping wound. I could have said, about the hands at the wake, that their desperate agitation sometimes sets in what, to my eyes, are comical or even obscene gestures. And, again: moving back and forth in front of the head of Mohamed's father, I see his features change, grow older or younger, go from an animal expression to a serene gentleness. What I know about how these works were made confirms that this dynamic vision is, of course, no coincidence. All the art of Pascal Convert and the sculptors who assist him, Eric Saint Chaffray and Claus Velte, consists in interpreting their model in such a way - correcting an effect of perspective here, and, if necessary, as it was for Mohamed, recreating the situation with living models - as to restore movement to these bodies that the photographs show as dead or prostrate. In the documentary about the making of the Pieta du Kosovo, we hear the artist doggedly insisting on this movement. During the production process, the clay stage - that is to say, the full relief sculpture made before the cast is taken in wax - terrifies him by its resemblance to a death mask or cenotaph. To convey what he is looking for, he shows a photograph of a medieval sculpture, a saint who seems to be breaking into a sprint, her coat rippled with folds. Another photograph pinned to the studio wall is a reproduction of a 20th-century masterpiece, Unique Forms of Continuity in Space, that is, Boccioni's walking man. Boccioni belonged to the Futurist movement. The least we can say is that Futurism was a movement that was "engaged" with its period. However, Boccioni's figure, endowed with wings or flames by his walking, can also be seen as the symbol of a man escaping his destiny. Like these people who, at the worst or last moment in their life, were photographed, and who are now transfigured.

Catherine Millet

1 - Festival Printemps de septembre à Toulouse, 24 septembre - 17 octobre 2004. Articles de Brigitte Ollier dans Libération du 28 septembre 2004 et de Michel Guerrin dans Le Monde du 30 septembre.

2 - Grasset, 1985.

3 - Dans le film documentaire de Fabien Béziat sur la réalisation de La pietà du Kosovo.

4 - Iris-Time, (l'artventure), Denoël, 1978.

5 - Manet, Skira, 1955.

/ Accueil /

Biographie / Oeuvres / Expositions / Films / Thématiques / Documents

Textes - articles / Editions / Liens - contact / Au hazard